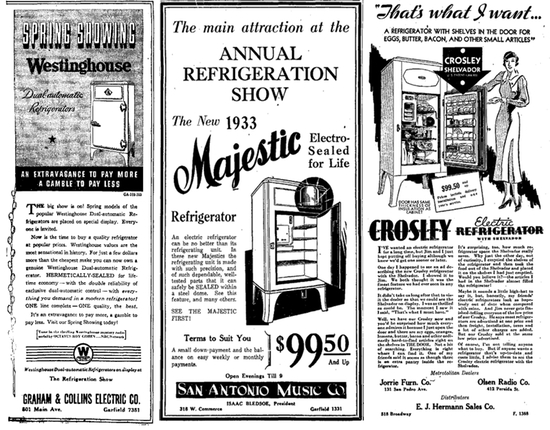

Refrigerator ads from the April 16, 1933 edition of the San Antonio Light (San Antonio, TX)

When I moved to Los Angeles and began my search for an apartment I was a little surprised by the fact that a refrigerator wasn’t included with most of the units I toured. In every other city where I’ve ever lived, the average apartment always included a refrigerator with the cost of rent. I was only looking for a one-bedroom apartment, but I was expecting that this was the norm everywhere for the most basic of apartments.

When I asked the manager of the apartment building I wound up renting from why there was no refrigerator, she explained that the property only supplies “the essentials.” When I pointed out that the building came with an underground parking space, she just stared at me blankly. It was in her silence that I came to understand a subtle difference between Los Angeles and the rest of the country: parking is essential, keeping perishable food fresh is not.

My belief that a refrigerator is an essential part of any home obviously comes from a place of tremendous privilege. For centuries, people have struggled with attempts at keeping food fresh. Only in the 20th century (after the first World War) did American consumers see the arrival of a slick new invention that would dramatically change our relationship with food; how we shopped and how we ate. But somewhat surprisingly, the rapid adoption of the electric refrigerator in American homes has its roots in an unlikely decade: the 1930s.

The Great Depression, despite all the hardships of the American people, would see the meteoric rise of the refrigerator. At the start of the 1930s, just 8 percent of American households owned a mechanical refrigerator. By the end of the decade, it had reached 44 percent. The refrigerator came to be one of the most important symbols of middle class living in the United States. While the upper class rarely interacted with such appliances, given the fact that they had servants, the middle class woman of the 1930s lived in a “servantless household”—a phrase you see repeatedly in scholarship about this era. The refrigerator was tied to one of the most fundamental and unifying of middle class events: the daily family meal. And it was in providing for your family that the refrigerator became a point of pride.

The refrigerator of the 1930s was often the color white, which people associated with cleanliness and proper hygiene. As Shelley Nickles notes in her 2002 paper “Preserving Women: Refrigerator Design as Social Process in the 1930s,” the whiteness of the appliance was supposed to signify that a woman cared about the safety and health of her family:

The refrigerator’s primary function, preserving food, was now linked visually to the responsibilities of the average housewife to provide a clean, safe environment for her family. Contrasting to diverse, localized practices of food preservation and wooden iceboxes kept in service areas and used primarily by servants, these white, steel refrigerators were conceptualized as part of the ordinary kitchen. By buying a white refrigerator and keeping it in the kitchen, the housewife expressed her awareness of modern sanitary and food preservation standard; her ability to keep the refrigerator white and devoid of dirt represented the extent to which she met these standards.

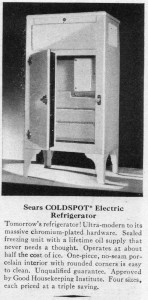

Ad for a Sears Coldspot refrigerator in the February 1932 issue of The American Magazine

The newspapers and magazines of the 1930s were filled with advertisements for the refrigerator—a luxury that was rapidly coming down in price. The advertisements above appeared in a 1933 edition of the San Antonio Light in Texas and show the hard push by advertisers to reach the middle class, despite tough economic times. That refrigerator advertised in 1933 as $99.50 would cost about $1,700 adjusted for inflation—not cheap, but within reach of families who might consider it a priority to feel a part of the aspirational American middle class.

The electric refrigerator was also touted as economical in the long term, after the initial investment. The advertisement at right appeared in the February 1932 issue of The American Magazine. Billing the Sears Coldspot electric refrigerator as “Tomorrow’s refrigerator!” the ad claims that it operates at half the cost of iceboxes:

Tomorrow’s refrigerator! Ultra-modern to its massive chromium-plated hardware. Sealed freezing unit with a lifetime oil supply that never needs thought. Operates at about half the cost of ice. One-piece, no-seam porcelain interior with rounded corners is easy to clean. Unqualified guarantee. Approved by Good Housekeeping Institute. Four sizes, each priced at a triple saving.

The magazine ad implored shoppers to shop at Sears because it was “The Thrift Store of the Nation.” Despite the rise of the modern refrigerator, the 1930s were an incredibly dark time for cash-strapped Americans. And yet here in the year 2012, I can’t imagine the refrigerator as anything but essential; much like an Angeleno’s car, I suppose.